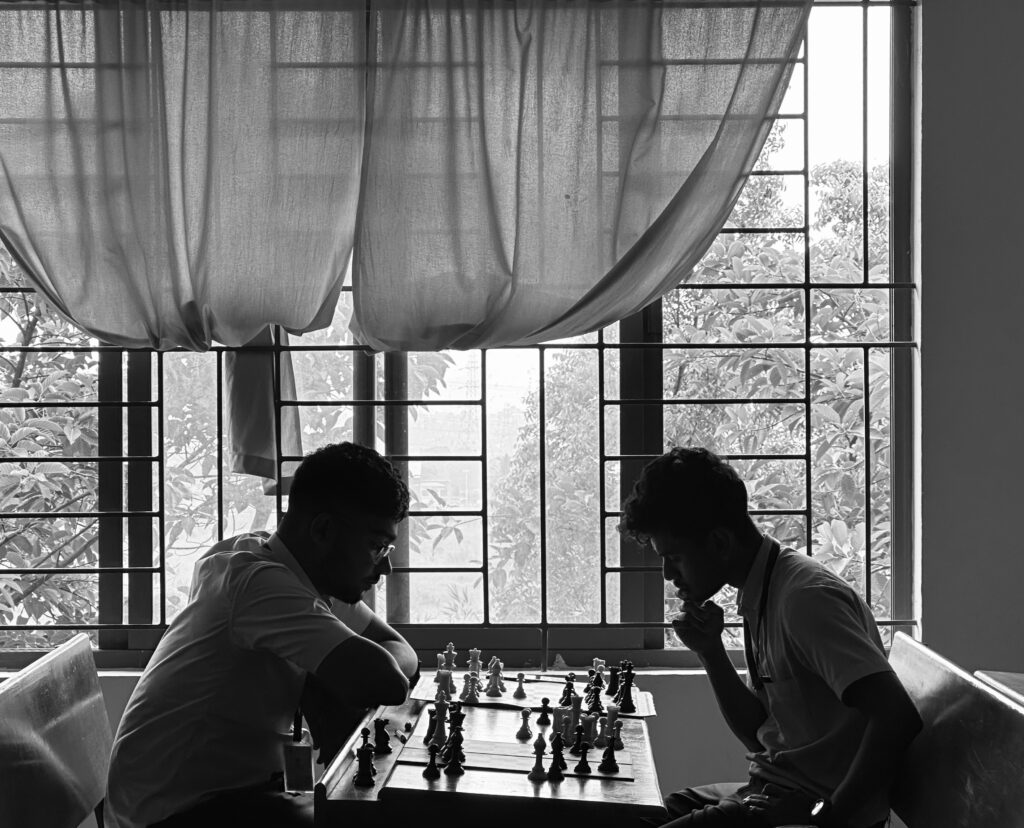

Walking into the S8 CE classroom one activity hour led me to quite the unusual scene. It wasn’t the conglomeration of students that took me by surprise but rather the display of numerous chessboards around the class, some of which were attended to by players whose unwavering concentration was seeping into their onslaught of observers. The air was heavy with quiet passion and dedication, an atmosphere ever so fitting for a sport as regal as chess.

It’s easy to mistake such a quiet and unassuming game as boring. I mean, it’s two people staring at a board moving a piece every few seconds, how exciting could it really get? And that’s where you’d be wrong. Chess is a game with many millennia of history, and you’d be surprised to know that for a lot of this time, it wasn’t the slow paced strategy game we’re familiar with. Chess started off here in India, with a name some of us might actually be familiar with, Chathuranga. The name was an allusion to the four divisions of the army at the time—the infantry, elephantry, cavalry, and chariots. So yes, that weird pointy piece is an elephant, not a bishop. The English started calling it a bishop as the projection at the top resembled a mitre, but that’s beside the point.

This strategic war game was a massive hit and later spread to Persia, where Chathuranga underwent a bit of a metamorphosis in terms of shapes and rules and became known as Satranj. Later, following the Arab invasion and conquest of Persia, chess was taken up by the Islamic world and spread to Europe, from where it would reach many parts of the world.

It evolved into the version we know today by around 1500 CE. Around the 18th century, the predominant style of playing was called Romantic Chess, which emphasized quick, tactical maneuvers to win the game rather than the slower, strategic method we see today. This period was followed by the Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism eras. Surprisingly, modern Chess tournaments didn’t start until the second half of the 19th century, and the first official World Chess Championship wasn’t held until 1886.

Getting back to our initial point, Chess is far from boring. Behind the slow movements and the quiet tournament are two brains working in overdrive—planning, predicting, and calculating every move while maneuvering 16 pieces to outsmart the opponent and attain the quickest, cleanest win. I had the chance to witness one such tournament.

Rajagiri’s small yet impactful chess team gathered around to compete against each other at the Inter-House Chess tournament held on the 21st of February. On speaking to Joanna Ann Manoj, S6 ECE Beta, she revealed that the Women’s Semi-Finals was a high stakes match, with her ultimately losing on time (a mere five seconds) to Neha Jaison from S6 CSBS. “I’m passionate, but not enough to be a Grandmaster”, she laughs. Joanna, like many of her peers, started her chess journey from a young age. However, it wasn’t until she joined the college team that her competitive spirit reared its head. Over the years, she’s represented Rajagiri at both the zonal as well as university level.

Sameera Sunil from S2 ECE Gamma emerged as the winner of the women’s finals. As a national rated player, confidence exudes her. Though quite young, her chess-centric family and upbringing gives her an edge over her competitors, many of whom are her teammates. Though Sameera finds it a little awkward to compete against her peers, she keeps a strong head in the game. On the battleground, she prefers to quietly react to her opponent, rather than aggressively charging ahead.

As the matches drew to a close, I lingered behind to speak to the men’s finalists – Anirudh Sai Krishna (Winner) from S6 ECE Alpha, and John Elmer Marokky from S2 CE, whose dynamic fascinated me. Their chemistry was palpable—from going head to head with each other over a chessboard to smiling and joking around after the match, their camaraderie shone through as one of the highlights of the match.

“I’m here to have fun”, says John Elmer, who happened to be a late bloomer. Unlike his peers, many of whom dipped their toes into the chess world at a young age, he admits that he is a comparatively less experienced player, having only started playing in 2021, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. His opponent Anirudh, on the other hand, grew up in quite the competitive environment, with a designated tutor coaching him at his home, as well as an encouraging father. Having grown up in Bahrain, he participated in numerous interschool tournaments. However, he acknowledged Indian chess culture to be more competitive, a factor he attributes to the deep rooted tradition of Indians honing their skills from a very young age.

Though the environment is welcoming, with most of these players surrounded by familiar faces, a certain element of pressure kept weighing down on them—the strive for excellence, and the drive to make their houses proud. Knowing your opponent well is a blessing as well as a boon. Your strengths and weaknesses are reflected right back onto you, driving the game into a higher plane of understanding. Yet, the very foundation of this duel is built upon the mutual respect they have for the sport they practice, as well as for each other.

In the end, the Inter-House Chess tournament at Rajagiri wasn’t just about checkmates and victories, it was a culmination of the passion and effort each student poured into a game that is often dismissed as boring and mundane. Each player— whether a seasoned professional or an amateur looking to try their hand in an organized competition— brought a whole new story to the board, which shaped their own path to victory. The calculated moves, strategic planning, and intense focus etched on the faces of each player, struck home the point I made in the beginning— Chess is more than just a boring assortment of movements and checkmates, it is a battle of two minds fought through the careful maneuvering of 32 pieces on a battlefield of black and white.

This newspaper is one of the amazing corners on the internet. Keep doing more of this Arundhati!